Audio Player

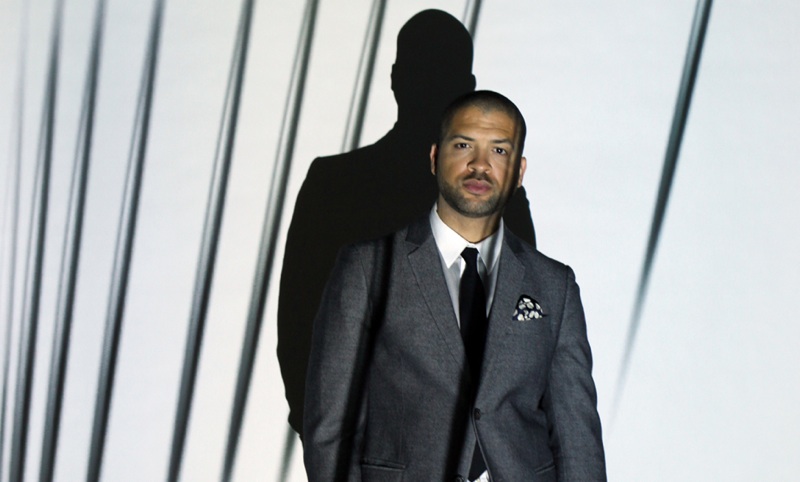

Jason Moran is a jazz pianist/composer based in New York. The MacArthur Fellow and artistic adviser for jazz at the Kennedy Center talks about when he first started improvising, how he collaborates with contemporary artists and what unfolded during Bleed, the suite of events he created with his wife Alicia Hall Moran during their 2012 Biennial residency at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Sound Editor: Leo Madriz | Known image credits noted | Music: Jason Moran, “He Takes His Coat and Leaves”

Related Episodes: How Jason Moran Amplifies Art and Jazz, Art With a Sense of Place, Part I

Related Links: Jason Moran, Bleed, Alicia Hall Moran, Whitney Museum of American Art

Episode Transcription:

CATHY BYRD: This morning, I’m speaking with Jason Moran, an amazing pianist/composer based in New York. Jason has toured and recorded around the world for twelve years with his piano trio, The Bandwagon. He’s a MacArthur Fellow and the artistic advisor for jazz at the Kennedy Center. I met him through artist Joan Jonas when they performed The Shape, the Scent, the Feel of Things at the University of Texas Performing Arts Center in Austin. Jason, I’m really excited that I get a chance to speak with you. I am particularly fascinated with the aspect of improvisation in your work. I work with visual artists a lot, and when I’m thinking of them in particular, I know that their audience, their collectors, their gallerists, their curators, are expecting them to establish a certain style that is unique but recognizable and maybe somewhat predictable. They improvise at first, and then end up setting a pattern. When did improvising become your pattern?

JASON MORAN: Within the jazz structure, the most important aspect is improvisation. I played Suzuki piano from age six to age thirteen, and it basically has no improvisation in it. At least, I didn’t feel any. I fell in love when I heard Thelonius Monk playing piano and understood that jazz is full of improvisation, that blues is full of improvisation. From that point on in my life, it was integral that I learned how to improvise, the language of improvisation, because within jazz there are many different languages to speak. Once you start studying the history of what has come before, just as a painter would study different painters from different centuries, then you understand the techniques. Right now improvisation is how I eat and live and breathe.

CB: When you’re talking about your collaborations with Joan, for example, you describe the importance of the relationship between the sonic and visual landscape. I’m wondering how those relational themes evolved in projects with other artists who you have worked with.

JM: With Joan, it was important to break the ice and not come in with any set plan of what the music would sound like, to watch and then see how the sound would come together in the space as I looked at her work. Whether I’m looking at quilts from Alabama, or a painting by John Biggers, or a video by Kara Walker, there are different ways of addressing how to give shape to the sonic landscape. One might be related to movement. Watching Joan is about movement and gesture. Kara Walker, her videos are more about this relationship to America’s social history and the pains that man goes through to hurt other men and women. In each case, you try to understand what kind of sounds are appropriate or can help underscore these stories, whether

they are abstract or very concrete and real. When I play with those notions, I decide whether I play atonally or I play tonally, or I play a song, or play an improvisation, or just play a groove, or just play a repeated figure. Learning that language then helps set the mood, the standard for what the new piece would be with these various collaborators.

CB: You were saying that with Glenn Ligon, you actually played the same song in a lot of different ways.

JM: With Glenn, that was what he was asking, almost like if we were going to do Goldberg Variations on a minstrel theme, in this case “Nobody,” a song that Bert Williams sang in 1906. That became an interesting topic to address musically, how to play a sound that would continue to evolve and not become redundant nor repetitive.

CB: As I was watching you and Joan perform in Austin, I was struck with the spatial dynamic. You were on stage, seated with your back to the audience. But, at many times, it seemed to me, Joan and the other performers were out of your view or at the very edge of your peripheral vision. I wondered how you established this sonic rapport with the unseen in that situation.

JM: Well, sometimes, the unseen is the unseen, and you hope to have some kind of dialog whether you see them or not. A lot of what I’m focusing on in the piece is the video because the music is not the action, it’s the landscape. In many ways, the video that Joan has, it also serves as the landscape, so I wanted to stay within those realms. I’ve never fully seen the piece. Even when I’ve watched the video of the piece, I’ve never really understood the whole aspect, because then I’m watching it on a screen. That makes a big difference. It’s like playing in a club with a band—it’s impossible to hear everything that everyone is doing. You can focus on a few things and then play to those things. But, then, after that, you have to be able to make sound and hope that it will all come together in some grand unified vision for the audience to experience. Sometimes it comes together, sometimes it doesn’t. But that’s the risk we play with as performers.

CB: How did the setting affect that dynamic at Dia:Beacon versus the small stage in Austin?

JM: In Dia, what was beautiful was that we spent months in there. We spent two or three months working on the piece and developing it. That made a big difference for us. What happened on the stage in Austin is we had a little bit of time. But, by that point we had a lot of history of performing that work. So, we understood how it works, what goes where and how, and then we could make adjustments. The beautiful thing is you make the adjustments and then those become the facts. It’s not about this myth of what Dia was; it was really only about how did Austin feel, how did it feel to perform this at the University of Texas. That’s what we tried to focus on, rather than the differences between the two spaces, because every space is going to be different. Even more than that, every audience will be different. Some people really want to engage and some won’t. This is how it is. To a degree, you have control, but to another degree, you have no control. Sometimes no control is good.

CB: That issue of the controlled space, it really played into your recent residency at the Whitney Museum, where you worked with your wife, mezzo-soprano Alicia Hall Moran. The project, which you called Bleed, had all these different live performances that were beyond jazz and opera completely. That must have been a very exciting process for you.

JM: It was very exciting to spend five days working in the Whitney, not only with my wife, with whom I’ve had a long relationship, but also with a bunch of other friends. It really became like a community project. People like Kara Walker would come and join us. Joan Jonas joins us. A columnist from the New York Times, Charles Blow, joins us. My band joins us. We have Taiko drummers join us. That became a really ongoing exploration of what our community is and the various kinds of output that we make, whether we are writers, dancers, singers, or musicians, or artists. Each artist decided to expand their boundaries in a way. Joan Jonas had never performed with my group, The Bandwagon, but there she was up on stage with us. Kara Walker had never done a musical performance before, and there she was up there singing and presenting a new work. That was how it unfolded. My wife was doing a piece with taiko drummers where she was singing a Beyoncé song. Everything was new. Everything was fresh. And we were presenting it to an audience that was accustomed to viewing work, a museum audience, a biennial audience. Within the grand scope, it was a wonderful five days.

CB: I imagine that the experience gave you ideas for other collaborations.

JM: Yes, it has. Most importantly: how do I transform the small work that I do with my group visually or aesthetically? How can I expand my repertoire on the stage, not only through music but through movement, through lighting, through costumes? That kind of thing is very exciting. That’s what I look forward to examining some more. People have already begun to write my wife and me about whether or not we will present a similar project in other places. It’s impossible to recreate what we did in New York, because New York is our home. So, there are other mutations that might happen in other places, but they won’t be Bleed. They will be something different. My wife and I are continuing to sift through the options that come our way, and in due time something new will happen.