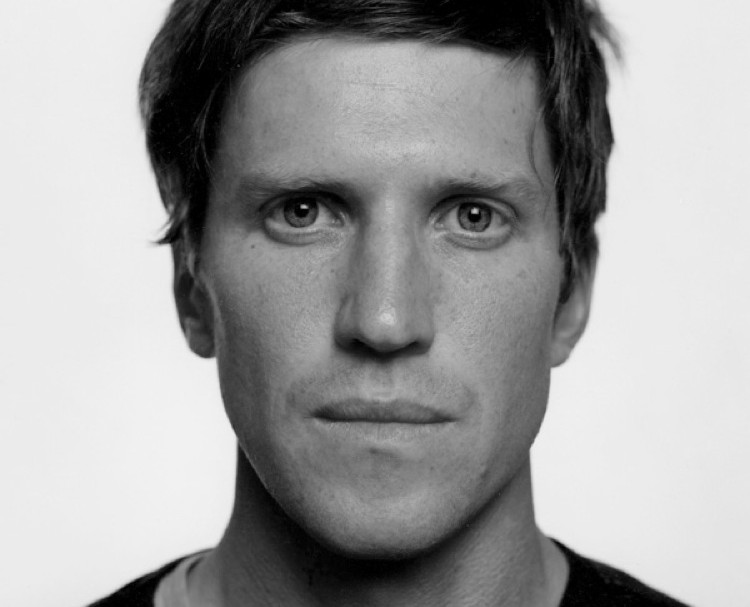

Adam Schreiber is Chicago-based photographer. Cathy Byrd meets him at an outdoor coffee house on East 5th Street in Austin, Texas. Adam talks about the sense of place that influenced his 2010 residency project at ArtPace San Antonio and how spatial dynamics affected the way he photographed the contemporary art collection of philanthropist and artist Linda Pace in her San Antonio residence.

Sound Editor: Eric Schwartz | Photos: Adam Schreiber | Episode Sound: Eric Schwartz

Episode Transcription:

CATHY BYRD: Today I meet photographer Adam Schreiber at an outdoor coffeehouse on East 5th Street in Austin, Texas. Adam’s passion is exploring collections, warehouses and archives. During his 2010 residency at Artpace in San Antonio, he pursued his interest in the dynamic between objects and the space that contains them. His installation of a DeLorean in the Artpace Gallery animated the building’s history as a former automotive plant. Context played when he photographed the contemporary art collection of philanthropist and artist Linda Pace inside her private San Antonio residence.

ADAM SCHREIBER: The project at Artpace was, in a sense, a way for me to use the architecture of the exhibition space to reflect on the architecture of the subject I was dealing with. Ultimately, that’s what the project became about for me. That’s what was ultimately important. It was, in a way, far more important than the subject of the pictures. The subject of the pictures, anomalous as it is, for me functions sort of like camouflage for the context in which the pictures are exhibited. While I’m interested in the DeLorean, I’m less interested in the car itself than its status as a placeholder. The Artpace gallery situation was an interesting container for that particular vehicle, which has a variety of cultural references and permutations, whether historically in terms of its fabrication or in terms of its history as a cinematic icon. With that preface, I think the Pace Foundation show took the idea of the context in which the pictures are exhibited to a different level in the sense that the pictures were exhibited in the space where they were made. There’s a circularity and there is a series of temporal riffs implicit in the work and the exhibition of the work.

CB: I spent time with Diminishing Returns, which was the Artpace project, and with this project that you did at the Pace Foundation. I noticed in both of those that there was a clear sense of staging and shadows, working with shadows and this super spare sense of color. This relationship you have with white and negative space gave the photographs themselves a theatrical aspect. And then whatever you chose to give color to became some sacred object. I think that’s a really interesting way of looking at a composition. To make one part of it stand out, you actually made all the other parts stand out by keeping them white.

AS: In a deep sense, I’m using the basic aspects of photography to expose the characteristics of the space. That space, as I mentioned earlier, is very specifically designed for someone to live with contemporary art and to have what I think of as a suspended perceptual relation to objects where literally in the visual field objects float in the space. That said, I think what Artpace director Steven Evans recognized about the way that I work and why I was interested in the space was that my particular process, using this really slow camera that records a tremendous amount of detail, had a particular relationship and potential for that space. So, the formal aspects that you referenced, and the reduced palette of color, came about pretty slowly and incrementally in the space. It came about through spending hours, literally, with particular scenarios of objects in the space. Though the ultimate pictures feel in some way very close to the only picture that could have been made of that, or the obvious picture, the ideal picture, that’s actually a process that one gets to as a maker of pictures and as a viewer. I think in retrospect that has an interesting connection to how the collector goes about establishing a relationship to their collection. Clearly, Linda’s interest in collecting work extended to viewing it. It wasn’t just about having the stuff. It was about an agitation, to create a space in which the characteristics of the work could persist in the most ideal context possible for as long as possible, creating, as you said, a stage for the work. Of course, every work is different and has different qualities. So certain qualities like color really come out in that space. And other qualities, like implied vibration: if works can make sound, even imagined sound, this is the kind of space that would allow that to happen. In fact, spending so much time there, just staring under the dark cloth at objects in the space, different things happen than being at a museum or gallery. This is still, in a sense, a private space. So those photographs came out of an unnatural or extended period of staring at an object. The exposures also tend to be quite long because of the technical aspects of the camera. So it’s not just a matter of looking at the situations for a long time, but it’s also this apparatus, this camera actually recording the scene onto large pieces of sheet film. These begin the process as a latent image and then become something like what I was seeing, but in other ways totally unlike what was seen. They become their own image of the space.

CB: In my mind, Linda Pace was the true subject of your investigation. Her domestic environment was designed to disappear, to fade away from the art that was the focus of her attention.

AS: On the one hand it’s a very designed space. You feel a sense of design to it, total design. But the effect of that is not ornamental. It’s design in the sense that you get into the synecdoche of the architecture of the space in relation to the architecture of the body, to the architecture of breathing, of how time passes, of how light moves across the space, your relation to gravity. Earlier I was talking about the role of the collector in the space, and how the space reflects the collector. As I

spent time there and as I’ve dealt with the pictures I made there, I’ve grown to appreciate this really active, restless relationship to art and the simultaneous desire to anchor or ballast that restlessness with the creation of an architecture that enforces it, as you said, that highlights the objects themselves. So if that’s anything like understanding Linda, it’s about understanding a feeling behind trying to see something and trying to hold something in your mind, trying to suspend perception long enough for an object to stare back and talk to you.